H

O M E • V

O R T E X 1 • V

O R T E X 2 • V

O R T E X 3 • V

O R T E X 4 • V

O R T E X 5 •

P E R S O N A

L B L O G

|

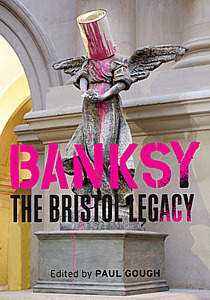

Publications

There are others who regard Banksy as a clownish one-liner, a prankster with attitude and a spray can. In his public statements Banksy cleverly toys with these disparate views, threatening on the one hand that ‘A wall is a very big weapon. It's one of the nastiest things you can hit someone with’ while raising Calvino-esque poetic aspirations on the other:

During the making of this book I heard a great many such stories, freely and generously re-told, often richly embellished, and resonating in ways that one would never expect to hear about ‘conventional’ pieces of art in a gallery. Many of these personal narratives were offered by people who had heard of the project and wanted, in some way, to be part of it. One woman volunteered this tale:

For those who left it too late they could always download the ‘official trailer’ on YouTube, which concludes with a PG Certificate and the warning ‘Contains scenes of a childish nature some adults may find disappointing’. As both a teaser for the show and the nearest we may have to an artist-sanctioned synopsis of the event it does seems rather authentic, except perhaps for one very short sequence (two seconds long, 54 seconds in) which captures at close quarters the figure of Sir Nicholas Serota, Director of the Tate, striding up the steep hill of Park Street ostensibly en route to the Banksy show. Sandwiched between footage of a hooded figure spray-painting through a stencil, Serota seems to be answering the question ‘What d’you think of Banksy’, to which an overdubbed voice answers ‘he’s frighteningly amazing’. Shot within inches of the Director’s face the words might actually be ‘frightening and amazing’. Whatever the words, they’re patently not Serota’s. By contrast every word in my book is authentic; the authors are happy to reveal themselves and to share their reflections of the show and its aftermath. The aim of this book was not to reveal the identity of the artist, nor to uncover how the show was created, although some of the contributors hint at both. Its aim was to try to evaluate the legacy of the show, to ask if there was an estimable impact, a lingering influence on Bristol, on its culture, on the museums, and whether this could be evaluated in economic terms. Clearly, the first port of call had to be the museum itself. Not the most settled of workplaces on the eve of the show, it had been blighted by a ‘staff-management dispute’ for some time that year as the then Director was leading a programme of re-structuring and staff ‘downsizing’ to meet wider budget constraints and realignment of the service. The show rather caught its own staff by surprise, many were delighted, a few though were actually unpleasantly surprised, feeling that their integrity as curators had been compromised by ‘intruders’ having the freedom of their collections. I recall walking past the museum on the Thursday evening before the unveiling and peering into the rather scruffily masked plate windows, taped over with sheets of paper, the doors labelled with A4 notices ‘Closed For Essential Maintenance Work’. We now know that the weeks leading up to those frantic few days of installation had been fraught indeed. Significantly, it started with a cold call from the artist himself. The curators who picked it up and ran with the idea were running a real risk; after all in mid-2009 Banksy was still an outlaw to many in the council. The waste and cleaning department had been irritated by the popular vote to preserve the Banksy painting of the naked man opposite the Council House. And although Banksy clearly had a deep affection for the museum recollected from his many childhood visits, his last public utterance about such places had been rather salacious:

It might surprise many to learn that a contractual agreement was actually drawn up between Banksy, his crew and the City Council. Graffiti artists don’t normally ‘do’ contracts. Civil servants don’t do much without them. However, without some form of contract Banksy couldn’t dictate his own terms and the museum would run the risk of being exposed should something go wrong. It can still be viewed online - all 14 pages of it - redacted (blacked out) in many places, and accompanied by numerous emails one of which begs the artist to ‘stay schtum’ as the museum and their lawyers clambered up the ‘mountain of work’ that faced them. Given the eventual success of the show it’s now hard to remember the actualities of the time. The stakes were high on both sides. Not only had the cultural chiefs closed their flagship building for over 48 hours without being able to tell their own staff why, but they had allowed what some might regard as a motley crew of hooded youth and ‘urban guerillas’ the freedom to roam at will amongst galleries of rather expensive paintings, rooms full of historic artefacts, and the largest collection of Chinese ceramic-ware in Europe. And, of course, they had no idea what to expect when the doors were opened to the public. Their story is retold in the book. They don’t, however, tell the full detail of the story and neither should we expect to have it revealed. Anonymity is essential to the Banksy myth. Still, it would have been fascinating to know how he and his crew managed to drag and assemble an ice-cream van into the lobby of the museum, or how they actually placed the orange-suited Guantanamo Bay figure in the middle of the flimsy balsa-wood box aeroplane that hovers over the main entrance. The ‘How Did He Do That?’ questions were never answered, nor did I really expect them to be. The curators had entered into a pact with Banksy and his crew which they did not want to compromise, not least because they might want to work with him and his team again, but primarily because they respected him and his team of fabricators, decorators, animatronic-ists, and installation professionals. A ‘reveal’ was not going to happen: that was the deal. That deal, however, didn’t stop national newspapers (allegedly initiated by The Daily Mail) from filing repeated Freedom of Information requests asking to see copies of any written correspondence, data, or transcripts of phone calls between the artist and the museum. Under pressure as a publicly funded body to release something, the museum eventually reproduced a heavily redacted copy of the contracts and an extensive sequence of email exchanges. Fascinating as these are they don’t reveal much, but they made a striking headline for the national press and pacified those in authority who feared that the council, the museum and the collection had been violated by the hoody and his crew. Yet how could this show not have proved so popular? The sight that greeted unsuspecting museum staff arriving for work on the opening day was the husk of a burnt-out ice-cream van. The choice was not random or a mere whimsy. In a BBC Radio 4 documentary on ice-cream vans in July 2011 Banksy, his voice heavily disguised, recalled with affection ‘the classic Bedford, gloopy tiny little row of headlights shining out from a droopy bonnet; yeah, it was made for selling ice-cream right? Because it looked like one.’ Adding, with characteristic edge, ‘it was a childhood thing gone wrong, really; slight loss of innocence, the broken shards of a burnt-out husk of Britain - but still with a soft centre.’ How could anyone not have warmed to an artist whose crew member told a journalist trying to get an interview ‘Sorry, Mr Banks is away polishing one of his yachts…’ Although some contributors suggest in this book that they know the ‘true’ identity of Banksy (indeed that ‘fact’ can be found within a few seconds of searching Wikipedia) the general public seems to have actually lost interest. By comparison, there is an increasing interest in how a large city like Bristol relates to Banksy, how he and his breed of artists speak for the city, and somehow represent a dimension of the city that is often difficult to quantify - its ‘spirit of innovation, creativity and unorthodoxy’ or what the UK Rough Guide describes as an unusual blend of ‘new technologies, the arts and a vibrant youth culture [that] have helped to make this one of Britain's most cutting edge cities.’ Cities however can easily forget. And as several contributors to this book loudly argue, Bristol has done its fair share of strategic forgetting. So, this book attempts to recall, remember and remonstrate with the easy amnesia that characterizes urban memory. It does so by asking several questions: what was the impact of the Bansky show in 2009 on the city of Bristol, on its earnings at the time and afterwards, on the businesses that benefited directly and indirectly from such a blockbuster show; what have been the mid- to long-term effects on the cultural sector in the city-region; what, if any, the impact on museum policies, direction-of-travel and its relationship to the community of artists that produce street art; what opportunities were missed (or taken) in re-positioning the city authorities and their relationship to its cultural players. The book suggests that there have been both some predictable and some unforeseen consequences to the show: in the more predictable column we might include the major street art show of 2011 - ‘See No Evil’ - and the annual UPFest (Urban Paint Festival) which have now become part of the Bristol zeitgeist; less predictable is the interest in issues of heritage and preservation, the move to recognise Banksy and his ilk as the creators of venerable objets d’art that must be looked after and valued as cultural markers. That could not have happened without the show in 2009, nor would the gathering of feisty street artists in Bristol museum during 2010 as part of a Research Council-funded project called ‘Design Against Crime’, which brought together a couple of dozen artists, gallery curators, Council community liaison officers, and academics like me squirrelled away in a corner taking notes and trying to understand the peculiar vernacular of tagging, buffing, and ‘green walls’. The gathering suggested how amenable (at least on the surface) the city of Bristol has become in the past five years to hosting street art, regarding it not as a curse on its architecture but an aesthetic gift to the public. It now takes the form of a ‘street dialogue’ in which the urban scene had become the subject and background of ‘an infinite flow of coded messages and interferences’. Artists such as Stic and Motorboy gave convincing and committed presentations, arguing that local authorities would actually save considerable sums of money if they courted urban painters, collaborating with them and with property owners to create dedicated spaces for their graffiti. Across the UK most councils had a reputation for being negative and hostile to street art, harassing and arresting perpetrators, painting over their work. The uniform grey of municipal censorship was described by one artist as ‘the greatest act of minimalist painting in the world.’ Each of the contributors to this book has addressed the question of legacy and impact. The first section of the book sets the scene, starting with a potted biography of the world’s most elusive artist by veteran correspondent John Hudson. This is followed by several essays that locate Bristol as a city with a rich history of radical dissent and division. Historian Dr Steve Poole discusses the hastily-scribbled or scratched calligraphic mark as the signature of urban protest, and in an essay on ‘the versus habit’ I trace the tensions that linger, and occasionally erupt, under the carapace of the city. The Banksy show, argues curator Kath Cockshaw, was preceded by an equally seismic event in an equally hallowed gallery. Her essay on ‘Crime of Passion’ concludes this initial series of essays that set the context for the show and identify its wider origins. The middle section of the book looks at the show itself. As principal architects of the exhibition Kate Brindley, Tim Corum and Phil Walker throw some light - though not the full beam - on their front-line role in staging the exhibition. One person who spent possibly more time ‘working the queues’ than anyone else that summer was the curator Katy Bauer whose innovative book The Banksy Q captured the raw enthusiasm and sticking power of the tens of thousands who travelled from far and wide to see the work. Her reflective essay locates the Banksy phenomenon in the widest political context and examines its roots in the Stokes Croft social scene. Eugene Byrne, a writer who few can match for his granular reading of the city, examines the immediate impact of the show and the artist’s ambivalent relationship with ‘official’ Bristol. Cultural impresario and historian Andrew Kelly offers a panoramic view of not only how the show immediately reverberated, but how it was also played out through a network of educational projects and associated events, which were deeply attuned to the many communities touched by Banksy’s work. Aware that many consider the artist to be little more than a witty one-line ‘quality vandal’, Kelly celebrates his more generous attributes and, as someone who also stages exhibitions, events and arts festivals concludes, ‘I long for the day when I can see those queues again.’ Which brings us to the third section of the book, where we attempted a judgment of the show from a number of vantage points. As someone deeply committed to bringing museum collections to life for the widest array of people, Dr Anna Farthing asks the knock-out question: who won? Her thoughtful and rhetorical answer is followed by a cool economic assessment by two business historians Anthony Plumridge and Andrew Mearman, who bring to bear evaluation and costing tool-kits to ask a number of questions about official statistics, hyperbole and civic sentiment. John Sansom explores one of the most visible manifestations of the Banksy legacy: the urban paint festival held in August 2011 under the rubrick ‘See No Evil’ which took place in an inner-city front-line urban trench sandwiched between new shopping arcades and rather threadbare office blocks. He discerns an official anxiety to appear inclusive and cutting edge, and also reminds us that in these excitable times the question should be not ‘is it art?’ but ‘is it good art?’ Another sceptical voice concludes this evaluative section of the book: with characteristic wit and an inimitable approach, art critic David Lee offers a sobering assessment of Banksy’s iconography. Drawing provocative comparisons with other ‘amateur’ art exhibitions held in the city more recently Lee draws some interesting broad conclusions suggesting that the 2009 Banksy exhibition may yet be seen to have marked a watershed in the State’s reaction to popular art. Drawing up the rear is an essay by lawyer John Webster who suggests that, given their cultural and financial value to a city, Banksy street paintings could benefit from the protection of listing through the British planning system. This is followed by a short essay on the art of stencilling, the urban calligraphy which has become Banksy’s trademark. A bibliography of further reading and viewing drawn up by Dr Alice Barnaby concludes the book. In truth, I could have included many other contributions to the book. Once word was out that I was embarking on this project I was inundated with stories, anecdotes, photographs and illustrations. The wave of generosity and interest was impressive and touching, although there were also those who wanted to express a controversial note and room has been found for these voices too. This is no hagiography. Arguing that Bansky is a pretty feeble rebel, David Lee argued that ‘if he were actually dangerous we wouldn’t indulge him at all. Instead of leaving him alone to continue his serial misdemeanours, the police, who are always supposed to be tracking him down, would have crushed him.” Yet, the Banksy story shows no sign of abating - it is lively, current and dynamic. The 2009 exhibition was just a staging post in a longer narrative about the city, its streets and its mutating identity, or as Banksy puts it:

Dr Paul Gough is the Professor of Fine Arts and Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the University of the West of England, Bristol. A painter, broadcaster and writer, he has exhibited widely in the UK and abroad, and is represented in the permanent collection of the Imperial War Museum, London, the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, and the National War Memorial, New Zealand. In addition to numerous roles in national and international higher education, his research into the imagery of war and peace has been presented to audiences throughout the world, and in numerous journals and books. He has published three books with Sansom & Company: a monograph on Stanley Spencer: Journey to Burghclere, in 2006; A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War was published in 2010, and Your Loving Friend, the edited correspondence between Stanley Spencer and Desmond Chute, in 2011. back |