H O M E • V

O R T E X 1 • V

O R T E X 2 • V

O R T E X 3 • V

O R T E X 4 • V

O R T E X 5 •

P E R S O N A

L B L O G

|

| Featured Artists

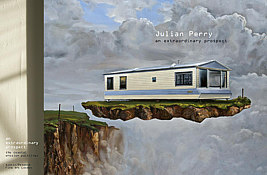

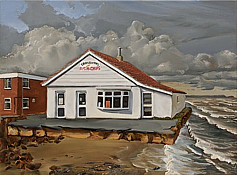

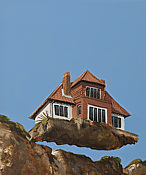

: Paintings of the Apocalyptic Erosion on Englandís Eastern Coastline : Julian Perry November 2010 with an essay by Paul Gough '‘A Terrible Beauty’: British Artists in the First World War'     Painting on the edge: Julian Perry’s paintings of the apocalyptic erosion on England’s eastern coastline To accompany Julian’s one-person show, London, Sept.-Oct.2010 Austin/Desmond Fine Art Pied Bull Yard 68/69 Great Russell Street London WC1B 3BN Incredibly, in a catastrophic eighty-year period (between 1328 and 1408) the churches of St Bartholomew’s, St Michael’s, St Leonard’s, St Nicholas, St Martin’s and St Anthony’s (a Benedictine Chapel) one by one toppled down the sandy cliffs of the once thriving town of Dunwich. A bustling East Anglian port of three thousand people, which had once been a mile inland, was diminished and denuded by the effects of what geologists term ‘longshore drift’. On occasion, the impact was indeed dramatic; a single storm in 1347 wiped out 400 dwellings, but for much of the time the effect was silently corrosive, the relentless impact of the tides making its gradual but inexorable progress through the town. Not that the townsfolk did nothing by way of defence. In 1540 the churchwardens of St John the Baptist sold off all the precious plate to fund a pier to stave off the sea. Alas to no end; the waters continued its western surge and the church went east. In an act of supreme defiance an entirely new church, St James, was built in 1832, but it too fell into the sea during the years leading up to the Great War, with the last stump toppling into the high tide the very day the Armistice was signed.     Dunwich, and its tormented topography, has become the capital of coastal erosion in Britain, the doyenne of those villages lost to the sea and now remembered for once being somewhere ‘over there’. Further up the coast in East Yorkshire, there are regular tours to visit the sites of two dozen villages lost to the sea in the 14th century but now reclaimed as a tract of salty land known sweetly as ‘Sunk Island’. There is of course nothing to see on the land or on a map, not even a single contour line, except their curious ancient names - Penysthorp, Frismersk, Orwithfleet, East Somerte. All gone, swept away by the waves, including one hamlet known only as ‘Odd’, memorable in the Guide Book for the line: ‘The history of Odd is short.’ As at Dunwich, it is difficult to know what to expect: there are no surviving stone walls, certainly no stone spires poking out of the reclaimed marshes, not a trace of centuries of habitation, nor evidence of an offshore English Atlantis complete with ancient sunken remains. Instead, there is an overwhelming emptiness, a backwater amongst backwaters under mother-of-pearl skies, a place of “dread fascination” but not one that lends itself easily to picture-making. Such was the prospect that faced Julian Perry as he embarked on his most recent odyssey to capture the volatile edge of modern Britain. Perry is one of our foremost landscape painters. An artist engaged in depicting modern man’s often uneasy relationship with the natural world, his most recent one-man show ‘A Common Treasury’, explored the doomed allotments that have now been subsumed by the 2012 Olympic site, and in 2004 he staged an exhibition that drew its inspiration from Epping Forest, London’s ‘threadbare back garden’, with its odd fusion of the bucolic and the urban, hubcaps trapped in trees, litter-strewn lay-bys, and large ponds formed from the craters created by mis-aimed V2 rockets at the tail-end of the Second World War. In fact, there is always something embattled about Perry’s landscapes, something adversarial, where natural elements come under unexpected duress, or sit uncomfortably in awkward juxtaposition. His is a landscape vision of latent violence. In one large painting from 2004, ‘Long Running’, Perry depicted a ragged array of silver birch trees, which had over time encroached on an open space threatening to destroy its unique character. It is a striking, quite singular painting. Not only is the central tree reminiscent of those fake periscope trees that were erected by Royal Engineers above the parapets of the Western Front, but it is surrounded by a deep trench of newly dug earth. Its function is simple, if somewhat surprising: one of the few effective ways of ridding a tract of unwelcome silver birches is to dig out the roots, exposing them to the elements through ‘perimeter entrenchment’. If this doesn’t work there is always the option (used occasionally) of blowing them up with explosives. Once again, Perry has drawn uneasy parallels with landscapes of war, creating places suffused with tension and expectation, drawing us towards outwardly becalmed and settled tracts that are in reality potent places of sudden noise, unchecked disturbance and hidden danger. Yet it was the very absence of these characteristics that surprised him on his painting forays up and down the beleaguered east coast. Instead of crashing cataclysm or booming birch, there was the banality of bungalows perched perilously on friable embankments. ‘Trees’, he said, ‘didn’t tumble spectacularly into the sea. They slid almost imperceptibly down on to the beach to be gradually washed away by the tides.’ How is it possible to convey the massive tragedy of such places, the profound loss of livelihoods and property, and the irretrievable vanishing of the very stuff that makes up the British Isles? We may indeed have been prepared to fight them on the beaches but what happens when the same beaches appear to be fighting us? Patiently and rigorously Perry set to work, hauling his painting paraphernalia many miles, to locate the motif that would best summarise the fraying edge of the country. The resulting subjects are sometimes totemic - an apparently fossilised tree standing proudly out of the sand, and another depicting one splendid erect trunk washed over by the surf (Sea Tree, Suffolk, 2009) - or they may be rather subtle, their tragedy captured in the image of an earthen bank incongruously peppered with fridge freezers. In others, the sheer pictorial juxtaposition conveys the magnitude of the catastrophe. In Suffolk Cliffs (2010) a 1920s villa, with exquisitely described red roof tiles, leaded windows and neatly maintained guttering, peers incredulously over a sloppy, fugitive bank of earth as if to guess at its inevitable fate. But Perry knows that exactitude cannot convey truth. Despite the sense of dramatic expectancy that pervades this work, despite the extraordinary violation and inevitability, Perry wanted the components of this landscape to have a future as well as a past, however ordinary. This explains, in part, the poetic decision to create floating forms that appear to freeze the land in time and space. Instead of sliding inexorably into fragmented banality, Perry offers us the remarkable prospect of poetic redemption. Instead of atrophy and collapse we are offered lightness and grace. In a leap of surrealistic imagining, which Paul Nash or Tristam Hillier would have instantly understood, the pill-boxes, 1920s semis, Fish and Chip shops and other seaside monumentalia have been salvaged from a briny doom, and lent an extended existence frozen, suspended, in paint on panel. Perry cites many precedents for his audacity. He takes no easy refuge in obvious comparators - Magritte perhaps, or possibly the Dymchurch paintings by Paul Nash - but points to those telling details in landscapes by Constable or Cotman, painters who also learned their trade on the eastern side of England, not far from the crumbling edge patrolled by Perry. ‘Look closely at a field of corn painted by Constable’, he argues, ‘you can actually see that it’s not quite ripe, you can feel the very moment that the breeze wafted through it. That moment is frozen in time, never altered since 1810, and I’ve always wanted to capture that temporal quality in my work.’ In his new paintings, Perry has defied nature in a way that Cotman or Crome could never have imagined possible, but he does so not to be sentimental, to mindlessly turn back the clock. There is a toughness about his work that stops it being maudlin or even mawkish. After all, it takes an unusual confidence to set up an easel within yards of some cliff edge calamity and peer into the misery of another’s disaster. Grayson Perry, in an insightful review of ‘A Common Treasury’ also identified this stubborn trait, this unwillingness to become nostalgic in the face of common tragedy. Much of Julian Perry’s robustness is achieved through the rigorous and deeply intelligent application of his craft. Capable of lovingly rendering any given surface - whether it be rusting Crittall windows or wispy cirrus stratus - he is not seduced by easy pictorial solutions; his formal constructions are tough-minded. Look for example at the handling of the tissue-like texture of the silver birch in the audacious Coastal Tree, or the suffusion of Indian yellow in the water-line of the foreshore paintings. Few British painters working today are capable of such subtlety, that ability to accurately describe the saturated density of recently eroded earth as it is stirred by each new wave. Perry has learned his craft by careful study of other Eastern England painters: he has determined that Constable created his distinctive painterliness by applying white pigment to one side of his brush and, say, burnt umber, to the other side, rolling and rotating his brush across the surface to create the remarkable effect of sparkling light. In certain of his own works, the fragment of Beach Tree, for example - he achieves equal effects, conjuring up the vivacious surface textures of Thomas Gainsborough or Jacob van Ruisdael. Indeed, the work of the great seventeenth century Dutch landscape masters spring to mind when savouring Perry’s oeuvre: his command of cumulus cloud formations owes a great deal to their example. Of course, in their work we have painters thriving on a flattened landscape reclaimed from the sea, while in Perry’s we have a landscape that is being reclaimed and flattened by the sea. To complement the temporal dimension in Perry’s recent work there is an inexorable spatial axis - the westward thrust of the ocean, the eastward slide of the land. Writing from the blighted ‘memoryscape’ of the Belgian trenches in 1915, T.E.Hulme, the Imagist poet and philosopher, noted how ‘in peacetime, each direction of the road is as it were indifferent, it all goes on ad infinitum. But now’, he added, acutely aware of how so much had changed, ‘you know that certain roads lead as it were, up to an abyss.’ To an extent, Perry has been working at a front-line, where peacetime rules have been reversed, and directions have become crucial determinants in sorting danger from safety, in discriminating those places that one can take refuge and those that offer unlimited views, or ‘prospects’. Perry (wrote William Feaver in an earlier catalogue essay) has a feel for in-between zones, for places where boundaries waver and enclaves are created. He has a natural affinity for liminal places that are caught in transition and flux, and his creative temperament is ideally matched to the chronic tragedy of the imperilled east coast. In these works he has created a new commemorative form, one not predicated on memorial plaque or inscribed stone, but one that re-institutes those doomed caravans and drowned pill-boxes to a guaranteed future suspended above the voracious waves, to live on in sun-blessed purity under those characteristically Perry-ian skies, while all around England frays at the edges, physically and (for much of the future) fiscally. Paul Gough Relate links: Catalogue : Painting on the edge (pdf) www.austindesmond.com/mbart/modules.php?op=modload&name=gallery&file= index&include=view_album.php&set_albumName=album1177 www.austindesmond.com/mbart/modules.php?set_albumName=PerryJ_exhibition-2010&op=modload&name=gallery&file=index&include=view_album.php Previous Featured Artists: Nicola Donovan Anna Farthing & Paul Gough Anthony Boswell Elizabeth Turrell Gail Ritchie back |