H

O M E • V

O R T E X 1 • V

O R T E X 2 • V

O R T E X 3 • V

O R T E X 4 • V

O R T E X 5 •

P E R S O N A

L B L O G

|

| On-line Papers

/ Journal Articles Paul Gough ‘That vile place’: the Beaufort Military Hospital, Bristol' Catalogue essay to accompany: Stanley Spencer, Heaven in a Hell of War, Pallant House Gallery, November 2013

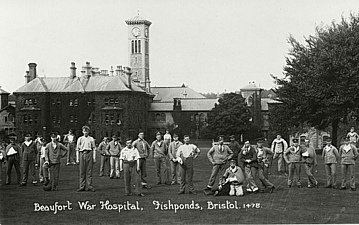

Bath, stand on the Railway platform & look towards a certain loathsome suburban church standing in the side of big hill. Take notes & get back into train. Get out at Bristol, on tram up to Fishponds. Go up a certain hill, a slummy street on left; small cottage, window-sill, on the windowsill earthenware animals & flower pots, on the other side of house small cottage garden on a steep slope, on opposite slope little orchard. Take notes and return to Cookham. Stanley Spencer 1 Spencer’s view would have been dominated by ‘a mad looking tower’; under the daunting gaze of its four huge clock faces lay a solid two-storey administrative block covered in ivy creeper (Fig. 1). 3 Stemming from these central offices emerged two wings each linked by corridors and internal passageways: the west wing housed female residents, the east wing males. Transecting the wings at various points were the two-storey ward blocks, and in between them a warren of connecting corridors, verandas and loggias that enclosed large leafy squares and courtyards - known as ‘airing courts’ - where the inmates took their daily recreation. Spencer would spend much of his time in the hospital pushing trolleys and dragging loads the length of these never-ending corridors, often under the watchful eye of the non-commissioned officers who made much of his time so fearful.

Frequent attempts had been made to soften the appearance of the asylum: in 1902, 2,500 potted plants were supplied by the estate gardener to the wards; a further 4,000 plants were installed four years later and the grounds were planted with specimen trees including several unique grafts so favoured by late Victorian horticulturalists. In 1912 the asylum’s Commissioners asked to see more pianos in the wards, and a year later central heating was extended to the male side. The building’s design was equally enlightened: rather than install oppressive metal bars over the ground-floor windows, the architect Henry Crisp had designed windows with cast-iron glazing panes giving an outward impression of normality but with maximum security assured. 4 Although the courtyard railings have long since been taken down and most of the metalpaned windows replaced, the old asylum can seem a grey and cheerless place. It must have appeared a chilling sight for the little-travelled and insular Spencer. By the time he arrived in 1915, the asylum had undergone a major conversion. 5 Like many hospitals across the country it had been requisitioned by the War Office, which had demanded 15,000 beds to be supplied nationally for war wounded. Forty-five asylum patients were retained to work the farm, the service departments and the kitchen garden, but the remaining 900 inmates were evacuated to rural asylums, some as far afield as Cornwall and Dorset. 6 Three months were spent converting the institution to house up to 1,460 wounded soldiers. Day rooms and night wards were converted into 24 medical and surgical wards. Corridors were made ready to take a further 180 emergency beds. Even the maximum-restraint cells - with their outward opening doors and steeply sloping window sills -were requisitioned for use. Throughout the asylum, rooms were adapted to act as operating theatres, radiography departments and pharmacy stations. Despite these significant alterations the hospital retained some of its prewar character, and wartime photographs of thewards show them with large potted plants and ornate furnishings, though little could disguise the hard deal tables, the flagstone floors and the high windows with their cast-iron glazing bars. In one memorable photograph Spencer can be glimpsed - a diminutive, slightly dishevelled figure in an ill-fitting tunic – surrounded by long avenues of beds, each separated by large wooden lockers, those very same lockers that Spencer and his fellow orderlies had to spend so much time scrubbing. Renamed ‘The Beaufort War Hospital, for the general medical and surgical treatment of sick and wounded soldiers’, many of the existing personnel were given new roles in the armed services. The Asylum Superintendent, Dr Blachford, became Lieutenant-Colonel RAMC, his horsedrawn cab replaced with a motor car. Physicians and surgeons arrived. A photograph from 1915 captures 19 officers, all but one - Jarvis - sporting a rather fierce moustache (Fig. 2). Spencer rarely encountered the officers. Orderlies, two to each ward, were at the very bottom of a complex nursing hierarchy - ‘onethird housemaid, one-third waiter and one-third valet’. 7 They worked under the authoritarian - and unchallenged - command of ward sisters drawn from the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve, supported by a cadre of nurses trained by the Red Cross. While no medical officer can be found on the walls of the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere, there are nurses in evidence: one appears in the canvas Sorting the Laundry. She may be the former asylum matron, Miss Dunn, whom Spencer found to be less intimidating than many others. Perhaps because of this he associated the laundry - which was lit from above by roof lights - with a church-like atmosphere. Despite the bustle, the heat and the noise, Spencer enjoyed an unthreatened peace in the laundry, one of the few places where he could gain some personal composure in the teeming metropolis of the Beaufort. Veterans of the Great War had little affection for the military hospitals: in letters and memoirs they complained of an inhumanity that seemed to increase with distance from the battlefield. At the front, wounded soldiers were treated by fellow-combatants and by familiar regimental doctors. ‘The wounded man,’ recalled one soldier, ‘is in a moment a little baby and all the rest become the tenderest of mothers. One holds his hand; another lights his cigarette. Before this, it is given to few to know the love of those who go together through the long valley of the shadow of death.’ 8 All this changed in the rear of the battle zone and in the general hospitals back in ‘Blighty’. Given the restrictions on wartime transport their journey from the front might be surprisingly rapid. Spencer’s brother, Gilbert, recalled his first terrifying moments as a medical orderly when he was confronted by a ‘ward full of wounded Gallipoli soldiers, their skins sunburnt and their clothes bleached and the soil of Suvla Bay still on their boots’ (Fig. 3). 9 Of course, the military had no intention of making hospitals appear too comforting; the intention was to patch up the wounded and return them promptly to active duty. Convalescence was not to be enjoyed; for many it was sour recuperation in grim and loveless surroundings, remembered bitterly for ‘Brutal injections … People nearly crying with pain. Gloomy buildings with bathroom taps all loose and tied to the wall with string … Meals never hot, worse than ordinary camp food and only served at strictly regulated times’. 10 There were a few diversions. Henry Williamson recollected: ‘Months and months of pain and contentment: regular grub and fags, military band outside once a week, and sometimes a theatre, riding in a toff’s car’, though he also described ‘[t]he terrible silence of the white wards, the swish of felt slippers, the terrible white walls and crying, the strange white sheets and beds in a row’. 11 In the paintings at Burghclere Spencer suppressed the muffled agonies of the hospital. His letters, though, are testimony to the casual brutishness and the uneasy tension between the wounded and their non-combatant guardians, with their ‘cushy’ jobs and protected status. Duty back in the front line became something of a release from the petty regime, harsh treatment and frustrations of the military hospital. Through the ‘Gates of Hell’ Passing through the ‘Gates of Hell’ at Beaufort signalled a change in Spencer:

me. A great clammy death seemed to be sitting or squatting on all my desires and hopes. Everything seemed so false. The day did not seem like day to me and the men did not belong to day. I felt that these beings, should they journey to where my home is, would evaporate into nothingness long before they got there. 12

been missed here & there. The ground was hard and had a ‘ring’ of iron about it, the lamp-posts, sign-posts, railings & the trees seemed to be ‘riveted’ to the ground: a steel-like uniformity prevailed & naught could prevail against it. 13

straight from a corn-merchant’s yard, a man used to heavy outdoor work’. 14

this … We had each to find our levels … in our own way. It was a case of every man for himself, and this instinctive feeling produced an atmosphere at once of unfriendliness between us. We each became to each other a symbol of our own helplessness. This consciousness, as those minutes dragged on, of a growing estrangement, was terrible, and all this to be happening in a big room rather like in feeling to the coziness of one’s own bedroom at home. 16

but not what one might expect. The lunatics are good workers & one persists in saluting us & always with the wrong hand. Another one thinks he is an electric battery.' 17

(usually a little up from the nave) … 4B was a bigger, darker & rather more convincing ward than M.I. … 4A was a long corridor ward with innumerable cubicles opening into it … I rather liked this 4B ward about 3.30 in the afternoon, which was the time when I usually took the dressing drums down to the polished steriliser somewhere at the end of a stone passage right over in the other wing of the hospital. When I started up this ward on this long journey I felt like some engine of a long train when starting to glide out of Paddington on a non-stop Irish Mail via Fishguard journey. Somehow I felt exhilarated that there would be no stops, & peace at each end. 18 the minutiae of the hospital would enrich the imaginary narrative of the Burghclere panels. In one of the predella panels, Washing Lockers, Spencer recalled the vivid colours of the cavernous washroom -‘six baths, about twenty hand basins, and a huge acreage of floor’ 20 - where ‘the baths were a deep sort of magenta colour and shiny, and when you had a row of them end-view on, they looked marvellous’. 21 Spencer’s recollection of surface and texture is quite astonishing, the passage of paint describing the coarse sacking of the aprons a tour de force, enriched by dense personal associations:

I would discover happy, homely places in the most unlikely places. There, only to mentally place myself between these baths and be scrubbing the floor is at once to feel inspired. 22

Possibly few other British painters of the last century have had such an understanding of the exact identity of inanimate objects. Peter Burra, one of the many visitors to the chapel as it was being painted, described Spencer’s ability to bring out the uniqueness of things as like a lover’s overpowering declaration of love for everything they saw in their partner or, in their absence, in their belongings. It was an intense, quite blinkered declaration that would brook no vagueness: it required (and invariably received) absolute clarity of visual expression. Indeed, Spencer himself believed that ‘To see anything imaginatively is to see a thing for the first time’. 24

Perhaps this explains the almost unique strangeness of Spencer’s personal vision. He tried to capture objects in paint through the fullest absorption of every thing ‘into’ himself. This was coupled with the recognition that the absolute identity of things - sheets, sponge, towels, taps, iron gates - was paramount because in that self-identity they were revealed to him as the ‘Forms chosen by God’. A common eye would have missed, overlooked and neglected the everyday things that became the spiritual nouns - the ‘burning bushes’ - of Spencer’s pictorial vocabulary. The Beaufort War Hospital teemed with such evocations, indeed it still does to this day (Fig. 5). Eric Newton expressed deep admiration for Spencer’s ability to proclaim and reclaim the distinct value of objects - whether it be a sponge, chair, kitbag, watch-chain or length of barbed-wire. Yet it was not just the ability to copy or reproduce distant objects with unnerving clarity, it was Spencer’s expression of them as ‘authentic fragments of autobiography’. 25 Kitty Hauser understood how he was capable of absorbing the very being of an object, its physiognomy, or the essentials of a gesture or a sense of place, and capture its internal equivalence. It might lie dormant for decades waiting for Spencer to retrieve (indeed ‘resurrect’) its essence in a drawing or a painting. 26 At the chapel at Burghclere, Spencer aimed to reconcile past and present through the act of pictorial reunification - a kitbag is reunited with its owner, an item of laundry with its wearer, a key for a gate, the quartermaster and his blankets, a resurrected soldier returning his cross. The murals are a hymn in paint to redemption and reconciliation, where the miraculous and commonplace are synergistic, the narrative ‘a mixture of an ordinary circumstance with a spiritual happening’. 27 Yet there was one final, and curious, element that Spencer left wholly unreconciled. Behind the altar-stone in the chapel, out of view to all but the most inquisitive visitor, Spencer painted a single beam of stone a yard long, lying on its side, a solitary rectilinear column of whiteness that rests somewhat forlornly at the foot of the great pile of crosses. Neither cruciform nor easily seen by the passing eye, what is it meant to represent? Is it - like the notch carved out of one of the larger crosses over the altar - an emblem of imperfection, a small piece of Spencer’s heaven-on-earth that would never be realised? Could this single beam of stone be a reference to Stanley himself, whose own cross could not have been fully formed as he was one of the survivors? Or maybe it is a sad reflection of his own loss of vision, his exhaustion after a decade of working with the memory of the war, another memento mori sent to remind us that, although the soldiers may have gained their individual redemption, Spencer would carry the weight of the Beaufort, Bristol and the Balkans long after he had left Burghclere. 28 Notes: Spencer first made a record of his war experience in 1919 (held in the Tate Archive as TGA 733.3.28). This draft formed the basis of a notebook written as he developed his ideas for the Oratory at Burghclere (TGA 733.3.84). The notebook was typed up in 1948 (TGA 733.3.85). A section was later added to this typescript (TGA 733.3.128). 1 Stanley Spencer to Florence Spencer, 27 June 1918, TGA 756.4 (the typescript of these letters is TGA 733.1.753). 2 See Donald Early, ‘The Lunatic Pauper Palace’: Glenside Hospital Bristol, 1861–1994: Its Birth, Development and Demise, Friends of Glenside Hospital Museum, Bristol, 2003; see also Paul Gough, Stanley Spencer: A Journey to Burghclere, Samson & Co., Bristol, 2006. 3 Stanley Spencer, ‘Account’, 1918, TGA 733.3.83. 4 Recreational activities at the asylum - and later while it was renamed the Beaufort War Hospital - included concerts, amateur dramatics and dances. The archive at the Glenside Hospital Museum, Bristol, contains several photographs of such events. 5 Initially, only 520 beds were required in Bristol for war wounded; 260 of these were to come from the Bristol Royal Infirmary; Southmead Hospital offered a similar number in its newly built wards. As casualties mounted these numbers had to increase, but the 1,460 beds provided at the Beaufort was the largest single contribution made by the city. 6 After the Armistice the vast number of the inmates returned from their evacuation to Bristol. 7 Lyn Macdonald, The Roses of No Man’s Land, Michael Joseph, London, 1980, p.150. Spencer wrote in one letter, ‘sweep wash & give bedpans 5 o’clock to 8 in the evening’. He added, ‘I would give anything to belong to the Royal Berkshires’ (TGA 8116.55). 8 Josiah Wedgwood, Essays and Adventures of a Labour MP, HMSO, London, 1924. 9 Gilbert Spencer, Stanley Spencer by His Brother Gilbert, Gollancz, London, 1961, p.137. 10 Arthur Graeme West, The Diary of a Dead Officer, Herald, London, 1918. Not for nothing were the RAMC sometimes known to front-line soldiers as ‘Rob All My Comrades’. Denis Winter suggests that the tension was due largely to the unexpressed guilt felt by the orderlies. Denis Winter, Death’s Men: Soldiers of the Great War, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1987, p.202. 11 Henry Williamson, The Patriot’s Progress, Geoffrey Blies, London, 1930,pp.189-91. 12 Stanley Spencer, ‘Reminiscences’, Glasgow, 1944, TGA 733.3.86, in Richard Carline, Stanley Spencer at War, Faber and Faber, London, 1978, pp.50-51. 13 'Reminiscences’, TGA 733.3.86. 14 Notebook/diary, 1915-18, TGA 733.3.83. 15 Notebook, 1944-5, TGA 733.3.85. 16 'Reminiscences’, TGA 733.3.86. 17 Stanley Spencer to Jacques and Gwen Raverat, July/August 1915, TGA 8116.54. 18 'Reminiscences’, TGA 733.3.86. 19 Notebook/diary, 1915-18, TGA 733.3.83. 20 Gilbert Spencer 1961, p.139. 21 Stanley Spencer to Richard Carline, 1928, in Carline 1978, p.182. 22 Stanley Spencer to Richard Carline, 1929, in Carline 1978, p.182. 23 George Behrend, Stanley Spencer at Burghclere, Macdonald, London, 1965, p.8. 24 TGA 733.2.3. Peter James Salkeld Burra left a short typescript that relates his experience of the chapel as it neared completion in the early 1930s. Given the title ‘Spencer’s Oratory’ by Richard Thompson of the Burra-Moody Archive, a copy is held at the Sandham Memorial Chapel. Though Burra writes with great beauty and insight, Spencer’s voice is also clear throughout. 25 Eric Newton, Stanley Spencer (Penguin Modern Painters), Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1947, p.9. 26 For a fuller exposition on the 'phenomenology of equivalence' see Kitty Hauser, Stanley Spencer, exh. cat., Tate, London, 2001, pp.73–4. 27 Stanley Spencer to Richard Carline, 1928, in Carline 1978, p.184. 28 So exacting was Spencer about the architectural detail of the chapel that as late as 1933 he was still fussing about small aspects of the design, writing to Mary Behrend in January 1933 that he still wanted a painted line to be added to the surface of the dado rail in lieu of a groove that could not now be cut into the plaster: ‘The grooves or lines divide the six feet widths of the predella picture into seven spaces.’ Stanley Spencer to Mary Behrend, 16 January 1933, TGA 882.8. See ‘The Holy Box’ in Gough 2006, p.196. top back |