H O M E • V

O R T E X 1 • V

O R T E X 2 • V

O R T E X 3 • V

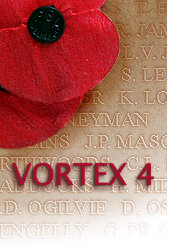

O R T E X 4 • V

O R T E X 5 •

P E R S O N

A L B L O G

|

| Featured Artists Cryptocephalus : Nicola Donovan November 2009 with an essay by Deborah Southerland    That has been. The word ‘history’ is etymologically1 related to the Greek ‘idein’ to see, and ‘eidenai’ to know, and this linguistic root is particularly pertinent in the context of Nicola Donovan’s work ‘Cryptocephalus’, meaning to conceal or to hide the head. Donovan has worked before with objects that depict or directly reference covering the head, that mask or allude to a blindness of sorts and in the context of this new work this lack of vision or ‘Cryptocephalus’ refers to Donovan’s sense of history, and her perception of the way in which the past is (de) valued in contemporary society. She asks ‘How can you map the future without looking to the past?…to disregard the past, to bury one’s head, is to try to build a house without a foundation or base - it will be an insecure and infirm structure, a structure without integrity… ’i Using Bletchley Park and the activities that took place there during the Second World War as a departure point, Donovan has used her sense of history and the responsibility she feels towards it as the fuel for this new body of work. Approaching the park, or ‘Station X ’ii as a memorial of sorts, Donovan knew she wasn’t interested in timelines or dates, it was detail that she was looking for, pieces and fragments of stories that could offer her an insight into the lives of the men and women who worked there. The work is the result of substantial research, but typically she hasn’t approached her subjects textually as a historian might, but visually and physically through sight and touch: as a maker, collector and translator. She has used this work to try and reposition herself within the past, to try and understand what she considers the un-understandable. Equipped with an empathetic drive and a finely tuned haptic2 instinct Donovan’s work is driven by the materiality of the objects she works with. Through the exploration and often quiet subversion of her carefully selected materials she engages in processes of practical, tactile remembrance. Objects in her hands are loved just as much for their aesthetic, as for being windows through which the past might be viewed, and on visiting her studio, observing the exquisite debris of earlier work, I was reminded of the way in which Walter Benjamin used expressions of touch and tactility to discuss ideas of experience and knowledge. ‘To touch the world is to know the world’ iii When the hand handles, it feels, and therefore it possesses a kind of authentic experience that can be deciphered and understood. Through touch one can gain a level of understanding about an object, its surface, material and form, an understanding that might begin to make explicit the object’s origin, the nature of its production or its intended purpose. In addition to this stereognosis3, Donovan’s imagination touches and is touched by the objects too, enabling her to begin her tender fabrication of narrative. This work is the result of a complex process of collecting, touching and thinking, and she has tended to her objects as if they were newly formed characters, gently coaxing them, deciphering their physical and emotive characteristics before summoning their quiet messages within the theatre of her practice. In a similar manner Benjamin relished Baudelaire’siv description of the poet as a rag picker, cataloguing the refuse of the city, he sorted, judiciously selecting and collecting refuse like a miser guarding treasure, treasure which in time and ‘between the jaws of the Goddess of industry’v would soon assume the shape of something useful. He applied the same image to his own method as a cultural historian, as a ‘connoisseur of ephemera,’ and it is an image that can be applied equally to Donovan’s methodology in whose hands these found and hoarded objects become narrative emblems that promise memory and knowledge, they become the vehicles through which she begins to guard against historical myosisvi. Each of her objects is individually codified, taking on meaning and reference as they are bought into (her) play. The reference to code is useful here as Bletchley Park was the location of the United Kingdom's main secret code breaking team, whose task was to crack the Enigma code and to simulate the machine with which Germany transmitted its secret messages. For Donovan this notion of code, this idea that something is not what it at first appears, provided an exciting aperture into new work. This is the Artist, who as a child used to sit beneath her stairs, working by torchlight, authoring her own secret codes: ciphers and symbols carefully drawn on to roll after roll of wallpaper. And though I have not seen these musings, I imagine them to be elaborate dialects, constructed through laboriously repetitive processes of writing and rubbing, writing and rubbing, inscription and erasure, emerging finally as palimpsests4, in the same way that the panels we see here have. That Donovan has chosen lace as her primary material not only references the Buckinghamshire lace traditions of the region; it also evidences her ability to exploit the double-edged connotations of a material. Culturally, lace speaks of Victorian uprightedness and local craft, but it can refer to slutty ostentation, the boudoir and transgression too, and Donovan enjoys its deeply ornamental yet unsettling double entendre. Structurally, it’s patterns are codified through symbolic motifs that speak of place, time and tradition, making the salvaged lace pieces that Donovan has used here loaded texts through which personal and local (his)stories have been encapsulated. These fragmentary pieces, indeed the panels themselves, are memorials of sorts. Mnemonic5 devices that shift in colour almost photographically, from black and white through to sepia, back to black and white again. Like the photograph, these panels do not restore the past, rather they summon it, attesting to it’s existence, and urging us to decipher what we see in the bruised lace displays. Lace is both ‘network’ and ‘web,’ a knotted twisted woven textvii of finely spun yarn, and textile processes such as this become perfect allegories for memory, alluding to the potentially infinite connections, criss-crossings and intersections that memory allows.    Drawing on the arachnid reference of ‘web’ it is useful to note that a ‘spider’ in lace making is the stitch commonly used to fill in the gaps between motifs, creating he ‘cobwebs’ that hold the ‘stories’ together. A ‘spider’ in computer terms is the programme that feeds search engines web pages, ‘crawling’ over the web indexing, sorting, cataloguing and archiving material. In this context Donovan assumes the role of arachnid, locating, collecting and indexing (pieces of) history and memory through her tactile and textile material language. Pinning and splaying her objects, (her subjects?) almost entomologically, Donovan uses this process to make her marks. She laboriously pins, and pins and pins, pinning and securing, as if this very process of piercing and fixing and securing could act as prevention against the blind myosis of forgetting. As if it could caution us to look, to lift our heads from the sand and touch these stories one last time before they slip fugitively across the border from here to forgotten. And here on the borders of forgetting alongside sable feathers and pinions of steel we find gas masks, salvaged masks that once covered the head, to conceal the face and safely seal the respiratory system. They offered physical protection from local particle aggression whilst enabling masquerade, performance of the Other and a type of internal escapism. Mandatory accessories from 1939 onwards these utilitarian rubber moulded objects are date stamped pieces of history. And unlike the lace Donovan found herself unable to unpick the masks, finding them too precious, too human, but like the lace the mask is delightfully loaded with overt and covert meanings, for coterminous with notions of safety, conformity and protection, are implications of blindness, punishment and shame; multiple translations of a deep internal text. The masks in Donovan’s work are themselves masked, doubling the concealment. Through lacy masquerade she pulls them away from their World War II roots, and drenches them in the decorative visual language of Victoriana, with flagrantly brazen lace crawling across their surfaces, insect like, theatrical, this shameless ornament soon becomes camouflage. And to complete this circular reference we note the linguistic relation between the word ‘camouflage’, coming from the French word ‘camofler’, meaning to mask or disguise, and ‘camofler’ probably being related to ‘camoflet’ which is a type of snubbing - or a blowing of smoke in someone’s face, thereby hiding it, concealing it and limiting their vision. Cryptocephalus indeed. And so we return again to the root of the word ‘history’ and it’s etymological relation to the Greek ‘idein’ to see, and ‘eidenai’ to know, and the idea that seeing and looking are intrinsically related to knowing and understanding. The struggle against forgetting is often the deepest motive of the person who collectsviii and Donovan has mobilized this ‘struggle’ not only honoring the objects in her collection, but honoring the past too. She has tenderly empathized with her subjects through processes of tactile enquiry and remembrance, and has used touch to help her see and understand. It has been a process of translation: the tender transmission of meaning from one (material) language to another, and a deciphering of that which has been seen and touched into knowledge and understanding. Deborah Southerland Artist and Senior lecturer in Design: Process, Material, Context at UWE, Bristol. Notes: i In conversation with the Artist. ii Bletchley Park was referred to as Station ‘X’ during the war. iii Leslie, Esther. Obscure Objects of Desire : Reviewing Craft in the 20th Century. Conference papers from UEA conference. 1997. P22. iv Charles Baudelaire was an influential C19th Parisian poet and critic. v Benjamin, Walter in Walter Benjamin’s Archive : Images Texts Signs, Edited by Ursula Marx, Gudrun Schwarz, Micael Schwarz, Erdmut Wizisla. Verso, London. 2007. P1. vi Myosis from the Greek muein, to close the eyes + -osis. vii The latin word for text: textum, translates as ‘something woven’. viii Benjamin, Walter. Arcades Project, Edited: Rolf Tiedemann, Cambridge. Belknap Press of Harvard. 1999. p.211 1 Etymology : the term used to describe the origin or history of a word. 2 Haptic : relating to the sense of touch, tactile. 3 Stereognosis : the ability to ‘read’ an object through physical engagement with it. 4 Palimpsest : A manuscript or text that has been written on more than once, with the earlier writing incompletely erased and often legible. 5 Mnemonic : from the Greek mnemonikós of or relating to memory. Previous Featured Artists: Nicola Donovan Anna Farthing & Paul Gough Anthony Boswell Elizabeth Turrell Gail Ritchie back |