H O M E • V

O R T E X 1 • V

O R T E X 2 • V

O R T E X 3 • V

O R T E X 4 • V

O R T E X 5 •

P E R S O N

A L B L O G

|

Reviews

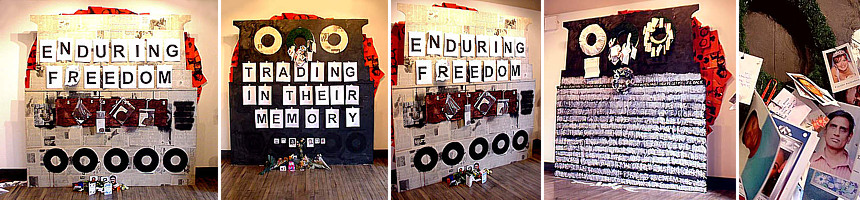

Paul Gough’s Faux Cenotaph: the contestation of rhetorical public space When Henri Lefebvre said that the Monument acted as a ‘consensus’, offering ‘a collective mirror more faithful than any personal one,’ and asserted that ‘everyone partook, and partook fully - albeit, naturally, under the conditions of a generally accepted Power and a generally accepted Wisdom’ , he overstated the case. Although the Monument appears to represent consensus, it may more properly be described as appropriating consensus, as it may be argued that most members of society do not see themselves in this ‘collective mirror’, rather they see a spatial and material expression of power. Therefore, if, as Christine Boyer has posited, memorials and monuments should be seen as sites of rhetoric , then the official monument or memorial may be calculated to be the ‘last word’, an emphatic statement of history according to the dominant ideology of its time. The essence of this kind of monument might be said to be silence: each monument standing as a polemical monologue that speaks in order to impose silence in the beholder, and, importantly, to maintain that position, in perpetuity, through the maintenance of Lefebvre’s ‘generally accepted Power’. Paul Gough had this version of the public monument in mind when his Faux Cenotaph [2001] was sited in a public thoroughfare in the Watershed Media Centre in Bristol, and when, simultaneously, across the docks in the Architecture Centre, he opened a parallel show of large drawings of monuments. His intention was to offset these works against each other, and in doing so he consciously referenced the commemorative landscape of Gallipoli, where Sir Frank Burnett’s imperial neo-classical monuments are contested by Turkish figurative memorials; each commemorative work oblivious to the claims of the other, and each speaking a history, that, in Gough’s words, ‘vies for the higher ground and for the moral ascendancy’. Gough has described the piece at the Watershed as a ‘false cenotaph’, and a ‘faux monument’. It had been constructed, perhaps, more as a work about commemoration than a commemoration in itself. However, due to the particular circumstances of its timing, coinciding as it did with the bombing of Afghanistan by America and its allies following the Twin Towers terrorist act in New York on September 11th 2001, it took on an unanticipated function. It became a temporary version of what the Germans call a ‘Denkmalen’: a monument that stands as a warning, causing us to meditate on the mistakes of the past, and hopefully to mend our ways. It also became a locus for the expression of protest. Through informal intervention on the part of the audience it became what I have described elsewhere as a ‘guerrilla-memorial’: a rejoinder to both the object and the genre of the monumental memorial. During the course of the 6-week show the Faux Cenotaph was written on, added to, subtracted from and eventually dismantled by its viewers. This monument, far from silencing the viewer with its rhetoric, seemed to incite intense, almost endless, ‘speaking’ from its audience. Inscriptions were regularly added to the piece over the period of the exhibition, epithets which included: ‘Trading in their memory’; ‘glorious’; ‘Enduring Freedom’, and at the very end for a few hours only: ‘BIG FUCKING BLUE’. Even the comments book became a part of its function as a collective, informal, denkmalen, or guerrilla-memorial, containing phrases condemning the bombings in Afghanistan, and the US war on terrorism, containing phrases such as, ‘this can’t go on’, and, ‘stop the bombing’. The historian Mat Matsuda suggests that commemoration is an act of evaluation, judgement, and of utterance. Gough’s work, originally intended to illustrate the notion of monument as monologue, now, due in some part to an extraordinary coincidence of timing, found itself engaged in the ‘polemics of commemoration and anti-commemoration’ , a situation common to many public artworks in times of extremis. The Faux Cenotaph, situated in a public place, was unlike many public monuments in that it seemed to invite intervention or participation. Perhaps because of its obviously temporary and contingent nature and its subsequent inability to claim ‘perpetuity’ or ‘authority’, it became a conduit for public comment on a contemporary and momentous political situation. The forms used by these guerrilla interventionists were sophisticated and knowingly applied: the typography mimicked the graphic conventions of the billboard, and engaged in wordplay linking commemoration with commerce. Each intervention made an opportunity for the next. The word, ‘FREEDOM’, became ‘F(-) EEDOM’ as another member of the public adapted and expanded the text. Gough also noticed that the inscriptions ‘played games with the high diction of official commemoration, what Samuel Hynes has called the ‘big words’ of civic remembrance’. These words: glorious, valiant, suffering, sacrifice, memory, peace, etc., more usually carved reverently in foot-high capitals in stone, were now represented in photocopies; serving as both parody and simulacra, their meaning subverted by medium and context. It is, perhaps, no coincidence that this six week long act of continual, sophisticated intervention with a public artwork took place in Bristol. The city has a long tradition of critical engagement with public monuments and memorial events. In 1997 the city hosted the International Festival of the Sea, in which Bristol’s maritime past was celebrated and acted out on the city’s docks, while the fact that the merchants of Bristol had African slaves as their ships most significant cargo was not officially acknowledged other than in a very subtle and powerful artwork/intervention, by the locally-based artist Annie Lovejoy, called Stirring @ the International Festival of the Sea. Although others have described this work as an ‘intervention’ , Lovejoy describes it as a ‘negotiation’. The key element of the piece was sugar. This commodity had been the main import in Bristol’s Triangular Trade. It had been bought from the profit of the sale of African slaves, and had been produced by slaves on plantations owned by Bristolian merchants. In Lovejoy’s piece spoon-sized packets of sugar were distributed to cafés around the festival site. The packets alluded to the Triangular Trade within the icon of the red triangle; a list of traded goods that included slaves; and an eighteenth century typographic rendering of the word ‘Bristol’. Also visibly present at the Festival of the Sea were the Bristol Chapter of the Guerrilla Girls. Their intervention with the festival was simple. Crudely photocopied posters depicting an eighteenth century plan of slaves packed into the hold of a ship were fly posted around the Festival and on signposts leading to it. As Felix Driver and Raphael Samuel wondered how we could ‘write histories which acknowledge that places are not so much singular points, but constellations’ and asked how we may ‘reconcile radically different senses of place’ , the visual and performic historical text that was the Festival was being challenged in its appropriation of the meaning and history of a particular place (Bristol in this instance) by the visual text of the fly-postered artwork. In the interventions with Paul Gough’s work at the Watershed we see the notion of public commemorative sites as possible sites of exchange come into play. It is significant that whilst Gough’s publicly situated Faux Cenotaph was the locus for furious intervention and ideological assertion, his companion piece on the same theme at the Architecture Centre, just yards away across the river, remained completely untouched during this same period. The fact that the ‘monument’ was situated in a public thoroughfare made it a public artwork in a way that the gallery -situated piece was not. The fact that it impersonated that particularly democratic form of memorial, the Cenotaph, which, unlike earlier monuments mourned the common soldier rather than celebrated the leadership of generals, and which is classless, rank-less and inclusive, meant that Gough’s cenotaph, faux or not, offered the possibility of reciprocation and inclusion. It is not, perhaps, too far a move from laying a wreath at the foot of such a monument, to, given the right circumstances, writing your contribution on it. The Faux Cenotaph gives us insight into the key differences between a public artwork and a public monument. This lies in a perception of the supposed inviolability of the monument as opposed to the contestability of an artwork. Casimer Perier summed up a common sentiment when he observed: Monuments are like history: they are inviolable like it; they must conserve all the nation’s memories, and not fall to the blows of time. Because of its simulant nature, the Faux Cenotaph does not, indeed cannot, maintain rhetorical power, i.e., the power to silence. Its temporary character, the fragility of its components and its consequent lack of civic or national authority, might be seen to open, rather than close, debate. Gough’s Faux Cenotaph is a simulacrum, it gives the appearance of being something, without containing that which is most potent in the original: in this case a sense of legitimate civic authority. It is not, and cannot be, the voice of ‘power’. Its actual affect comes from its function as art rather than as a civic or national monument. In this it is, in itself, an example of the continued contestation of rhetorical public space. April 2003 References: Lefebvre, H. ‘The Production of Space (Extracts)’ in Leach, N. (ed), 'Rethinking Architecture', London & New York, Routledge, 1997 p139 Boyer, M. C. 'The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments', Cambridge Massachusetts & London England, MIT Press, 1996, p343 Matsuda, M.K. 'The Memory of the Modern', New York & Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996 p6. Nash, C. ‘Historical Geographies of Modernity’, 'Modern Historical Geographies', Edinburgh, Prentice Hall/Pearson Education, 2000, p34 Driver, F. & Samuel, R. ‘Rethinking the Idea of Place’, History Workshop Journal 39, pvi Michalski, S. 'Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage 1870-1997', London, Reaktion, 1998, p78 Perier, C., cited in Matsuda p33 Sally Morgan is Professor of Fine Arts at Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand. top back |